By Cathelijne van Andel and Vail Zerr, class of 2021

As part of the Master Heritage Studies, the class of 2021 travelled to Copenhagen, Denmark to research and participate in an interdisciplinary course regarding the heritage transformation of the Frederiksberg Hospital. After a memorable journey on the ever-reliable Deutsche Bahn, marked by delays, card games, and the construction of suitcase-sofas between train carriages at the loss of our seat reservations, we arrived in Copenhagen energized for the two weeks ahead of us. Excited to flex our heritage muscles in action alongside the team of KU landscape architecture students, we spent our introduction days bonding with colleagues and visiting various sites of transformation in Copenhagen including the Carlsberg Brewery, Nordhavn, and Christiania, before diving into our study site.

Built in 1903, the Frederiksberg Hospital has been expanded several times over the past century. Today, it’s reaching the limits of space. In the beginning of the twentieth century the hospital was situated on the outskirts of the city, but it has gradually been incorporated into the urban environment as the city grew. In 2010, the owner of the site, the municipality of Copenhagen, decided that in a few years’ time the hospital will be housed elsewhere, allowing the existing landscape to be transformed into an urban living and working area. To date, the handling of heritage within this transformation has been approached hierarchically, and is seen as one of the many elements that had to be researched independently and objectively within the planning framework. Thus, before the architectural firms Tegnestuen, Vandkunsten and Effekt could start on the design, the ‘heritage’ box had to be ticked off first. A study was then carried out in order to individually value the site’s heritage buildings. From our critical heritage perspective, it was intriguing that only the oldest and most ornate buildings were regarded as worthy for preservation (based on a traditional outlook wherein architectural ‘masterpieces’ are musealized and the other buildings and structures are omitted).

Combined with the Danish landscape design students, and architectural history students, we heritage students were given an assignment to analyze the historical development of this site and cooperatively develop visions for the future of the area. Each group was tasked with producing a proposal for transformation that would have a positive effect on the long and short term success of the new site. Although it was a fun and academically stimulating experience to work within this international and interdisciplinary setting, it also posed its challenges. After a year of studying heritage, the theory and spatial approaches that seemed obvious to us were not so straightforward for the landscape design students (and vice-versa). Our fields were complementary, but not the same. Yet, after two weeks of fieldwork, research and lively discussions, each group successfully presented comprehensive handouts and interventions for a jury of students, professors, and representatives of the Frederiksberg Municipality.

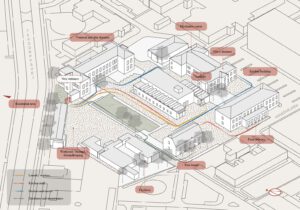

Our aim was to further develop our understanding of heritage, translate our theoretical insights into practical recommendations, work closely with the field of design and inspire the municipality to be more aware of the heritage values of the site. As such, each group pursued a different zone, theme, or narrative within the site, crafting their presentations from a unique blend of historical and spatial interpretations. My group (Cathelijne) placed emphasis on the social history of the western corner of terrain. Historically, this corner was the ‘back end’ of the site, both spatially and socially. Patients of the lowest social classes were treated and housed here. For example, there was a clinic for sexually transmitted diseases, and a poorhouse for the homeless. Other unglamorous functions, like the laundry, kitchen and facilities were also tucked away. The still existing landscape of the site, with the buildings, spatial structures and elements, tells the story of the daily life of the hospital. Because of this history, it wasn’t surprising that this corner was valued the least worthy for preservation by the heritage division of the municipality. Our group saw something different. The daily life of the workers and the patients is one of the many historical layers of the site worth telling. We believed that the heritage value of a ‘healthcare landscape’ is as much about social history, as it is about the nicely decorated architecture. Our group paid attention to the social history by proposing a new entrance and visualizing the routes of hospital staff in an art installation.

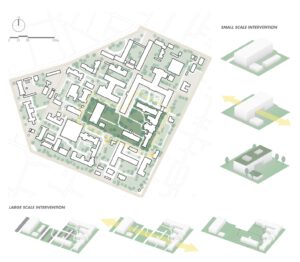

In a different approach, my group (Vail) found that the Frederiksberg Hospital site lacked a visual and spatial centre. We therefore opted for the treatment of a cluster of 1970s laboratory buildings situated in the approximate centre of the site. We were fascinated by the somewhat automatic aversion to the architectural aesthetic of these buildings amongst our peers (which was not aided by a complete disconnection of the site’s beloved greenspace by way of excess parking lots). Yet, we considered the ‘young’ heritage to carry immense potential for sustainable transformation. Thus, through a process-oriented participatory intervention, we argued that while this more contemporary and less ‘romantic’ architecture might be overlooked in heritage discourse, it greatly lends itself as a ‘blank canvas’ for new use. Through various degrees of public participation in temporary to permanent phases of this transformation, we ultimately aimed to positively reshape the narrative of these contested buildings, reconnect surrounding greenspace, and create a central generator for social interactivity for the future of the entire site.

And so, with our days spent discussing landscape, heritage, and where to find the best Danish kanelbullar, and our evenings spent catching up on thesis writing or with friends in the Nørrebro neighbourhood, two weeks in Copenhagen quickly passed. It was clear that this new practical academic environment highlighted what we knew as heritage students – and perhaps more importantly, how much more we can learn. The diverse combination of our respective disciplines sparked engaging debates on the role of heritage in cases of transformation as well as how we can inform one another in the interdisciplinary environment. From each conversation, and each step in the process, we certainly gained new perspectives on our field, and on our role as heritage professionals within broader spatial practices – lessons that will prove invaluable as we prepare to graduate this fall. Thank you again to Linde Egberts, Bettina Lamm, our new Danish colleagues, and of course, all of our friends in the programme that made not only this trip, but this year, unforgettable!