by Steffie van der Weijden, student Heritage Studies

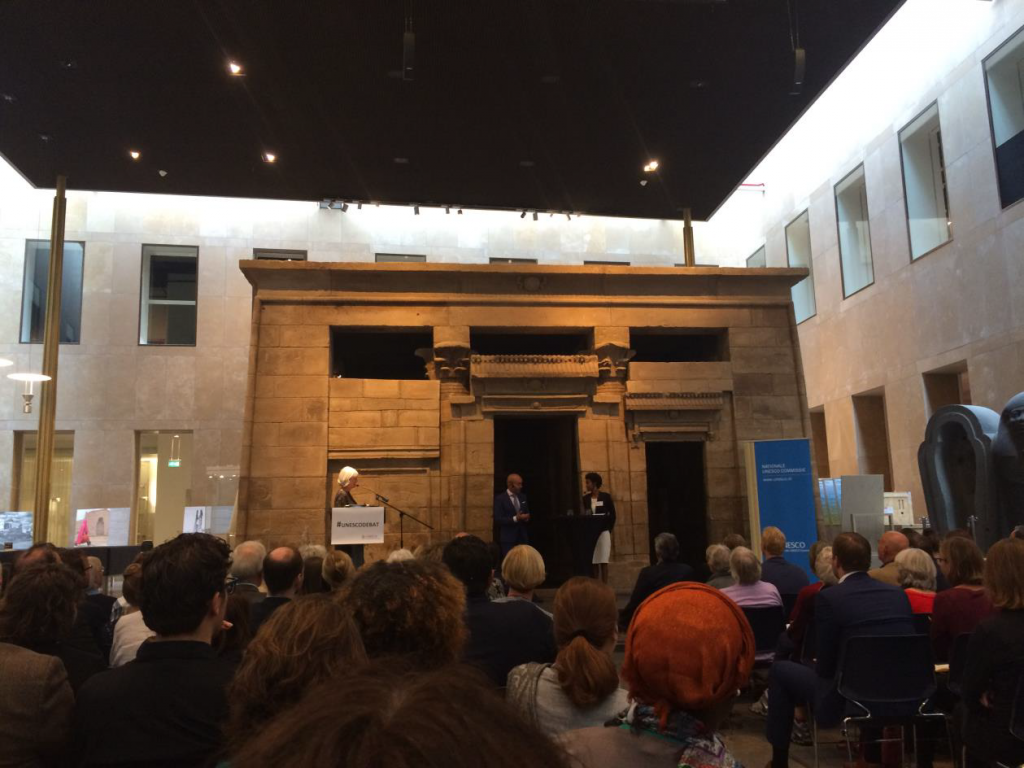

On the 29th of September I attended the first UNESCO-debate, held in Leiden at the ‘Museum voor Oudheden’. The event invited two speakers to talk about the consequences of pointing out world heritage in war zones, in response to the ongoing destruction of Mosul by Isis. The first speaker is a Dutch columnist, political scientist and filosopher, Stephan Sanders. The second speaker, Sada Mire, is the only active archaeologist in Somaliland. After both speeches the two speakers engaged in a short debate, led by chairwoman of the national UNESCO committee, Andrée van Es.

In his opening speech Sanders focused on the importance of having world heritage to establish a certain universalism for mankind, the creation of a global uniting history. UNESCO was created with the vision to unite nations by their shared cultural heritage and prevent another world war from happening. Sanders’ point of view on world heritage can be described as large scaled and top-down. The protection on heritage by UNESCO helps to develop a universal history which will contribute to world peace.

Mire in her responding speech agrees with his view that world heritage should receive protection, but supports this statement not large scaled and with a top-down view but with a bottom-up point of view on a small scale. In her opinion heritage is a big part of regional identity and, even smaller, individual identity. She said that protection by locals rather than by UNESCO would work better, because it is part of their history and that is why they are strongly connected to it. She also expresses that the destruction of heritage has always been a problem.

The closing debate was supposed to be about the question if world heritage is either a treasure or a target, but in fact they only briefly attended that problem in the last five minute. Both of them said that it is a target as well as a treasure. They both felt that world heritage should be shared with the world, but that we should be more aware of the political consequences of the UNESCO world heritage list.

Then someone from the audience asked if they thought that the UNESCO list turns the heritage on it into superstars, or that the heritage already had superstar status and therefore is added to the list. Sadly, they didn’t answer the question at all. In my opinion, it differs for every heritage site. In some cases, like ‘Schokland’, it may have had superstar status viewed by experts, but was not known to the big public. The UNESCO label draws attention to the site, through which it gains superstar status. Other cases, like the Pyramids or Machu Picchu, are obviously extraordinary and through their qualities they cannot be absent on the list. So by pointing heritage sites out as stars, it wouldn’t necessarily make a difference, because they could have been stars already through the eyes of, for example, local communities. Therefore I think that every heritage site is a treasure, but adding it to the world heritage list of UNESCO does not always turn it into a target.

Maybe heritage can play another role, one of building bridges. By realizing what men was capable of in the past, it could help us see what we could be capable of in the future if we set aside our differences. I would like to conclude this reflection with the words of Mire, which contain a challenge and opportunity for heritage: ‘if we can accept difference and diversity in our own past, we can accept difference and diversity in our present’ (Sada Mire, personal communication, 29-09-2016).