The Dutch national government addresses the issue of the societal value of heritage in its report ‘Erfgoed Telt: de betekenis van erfgoed voor de samenleving” [Heritage counts. The meaning of heritage for society]. With this report, the government invests quite 325 million euros in the preservation and accessibility of heritage, meaning the outreach to all Dutch inhabitants. Heritage is seen as a potential connector in society. That is of course a great ambition, but it lacks awareness of the selectiveness of heritage. During a lecture at the National Monuments Conference, held in Amersfoort on November 6th 2018, I argued that heritage professionals have a core responsibility in becoming aware of their role in the selection of heritage. This way, they can make a true difference in turning heritage into a tool for inclusiveness.

Does heritage really unite people by offering an anchor for identification with a shared past? Not if we ask Laurajane Smith, who argues that “there is really no such thing as heritage” (Uses of Heritage, 2006, p. 11). She does not mean to say that there are no historical landscapes or buildings, but she argues that they do not carry any intrinsic heritage value. Things are only heritage if people attach heritage values to them. This process of heritage selection usually takes place in what she calls the “Authorised Heritage Discourse”, or shortly AHD.

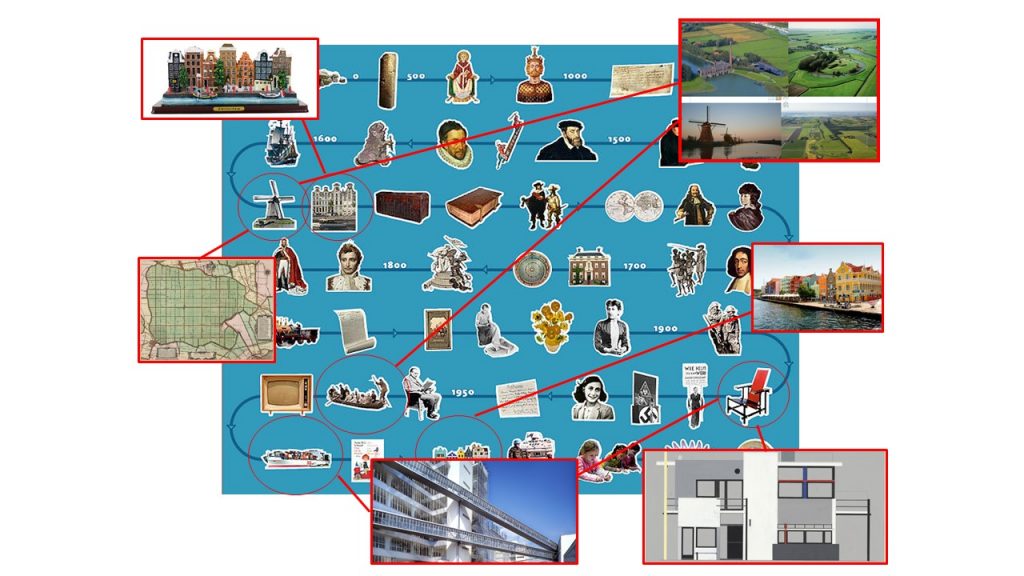

And example from the Netherlands: The Dutch sites on the World Heritage list show great parallels with the Canon of Dutch History. This is no coincidence, as both the heritage sites and the canon’s windows are somehow supposed to be representative of the most important parts of the Dutch national history. To become aware of the AHD here, we only need to ask: what is not on those lists? Which histories, places and people have been left out?

The Colonies of Benevolence form a great start to an answer. Recently, these colonies became a candidate for the cultural landscape category on the UNESCO World Heritage List, but were not (yet) admitted to the List. That is a pity, because it could appeal to different audiences than the current listings for several reasons:

- this site represents the history of common people: 1 million Dutch citizens are claimed to decend from inhabitants of the colonies. It thus offers anchors for identification for many through direct family ties.

- Moreover, the Dutch colonies are situated in the provinces of Drenthe and Overijssel. They represent other landscapes than those created in the struggle with and against water that is so dominant in the narratives about Dutch landscapes (and that only represent one part of a very complex and dynamic history). (In her recent inaugural address, prof. Lotte Jensen presented a critical review of the role of the water narrative in Dutch nation building)[1]

- The colonies are the first international candidacy for cultural heritage, as the listing also includes two Belgian sites. This is valuable, as it illustrates how international Dutch history actually is, just like many of its inhabitants.

- The colonies represent a dynamic landscape that has evolved from its original ideology and function, but still shows many historic ties to its origins. This candidacy thus represents a dynamic interpretation of cultural landscapes that is quite different from classic, sectoral monument preservation.

Veldzicht, Balkbrug in 1999. The complex is currently used as an a transcultural psychiatric institution. Image by Rijksdienst voor het Cultureel Erfgoed, released under Wikimedia Commons.

Veldzicht, Balkbrug in 1999. The complex is currently used as an a transcultural psychiatric institution. Image by Rijksdienst voor het Cultureel Erfgoed, released under Wikimedia Commons.

image by Nationaal Monumentencongres 2018.

Unfortunately, this last point appeared to be the candidate’s Achilles’ heel. The sites were not (yet) listed as World Heritage, primarily because ICOMOS argued that the authenticity and integrity of the original ideology and function were not preserved on an outstanding level, despite the fact that the current uses reflect unique, dynamic, living landscapes. Here we see the difference in interpretations of ‘heritage’ and ‘landscape’, played out on the highest, international stage. Heritage professionals thus play a central part in deciding whose past becomes heritage, and whose is left out.

This brings me back to my central point: heritage experts and their decisions play a key role in deciding how inclusive heritage really is. The knowledge they share and the ways in which they communicate are central in the shaping of the Authorised Heritage Discourse. That is why it is extremely important that platforms like the National Monuments Conference address this issue. What is on the list and what is not? Who gets the authority to speak and who doesn’t? Who gets to attend, and who is not invited? Let it be clear that we way we select now is decisive for the heritage of our future.

[1] Jensen, L. (2018). Wij tegen het water. Een eeuwenoude strijd. Vantilt, Nijmegen.